- Water and Electrolyte

- References

Water and Electrolyte

The goal of drinking during exercise is to prevent excessive (>2% body weight loss from water deficit) dehydration and excessive changes in electrolyte balance to avert compromised performance.

However, the history of water balance has been evolving. There was a time (in 1990s) people thought 100% replacement of water is critical to duration sports. However, that requires a lot of drinking, which isn’t realistic in many circumstances (the water loss rate is so that, while body’s absorption rate can barely catch up, or requires a full stomach of liquid). Plus, lack of electrolyte can also be harmful if not being thoughtful.

World best marathoners can lose ~9.8% body weight in a race

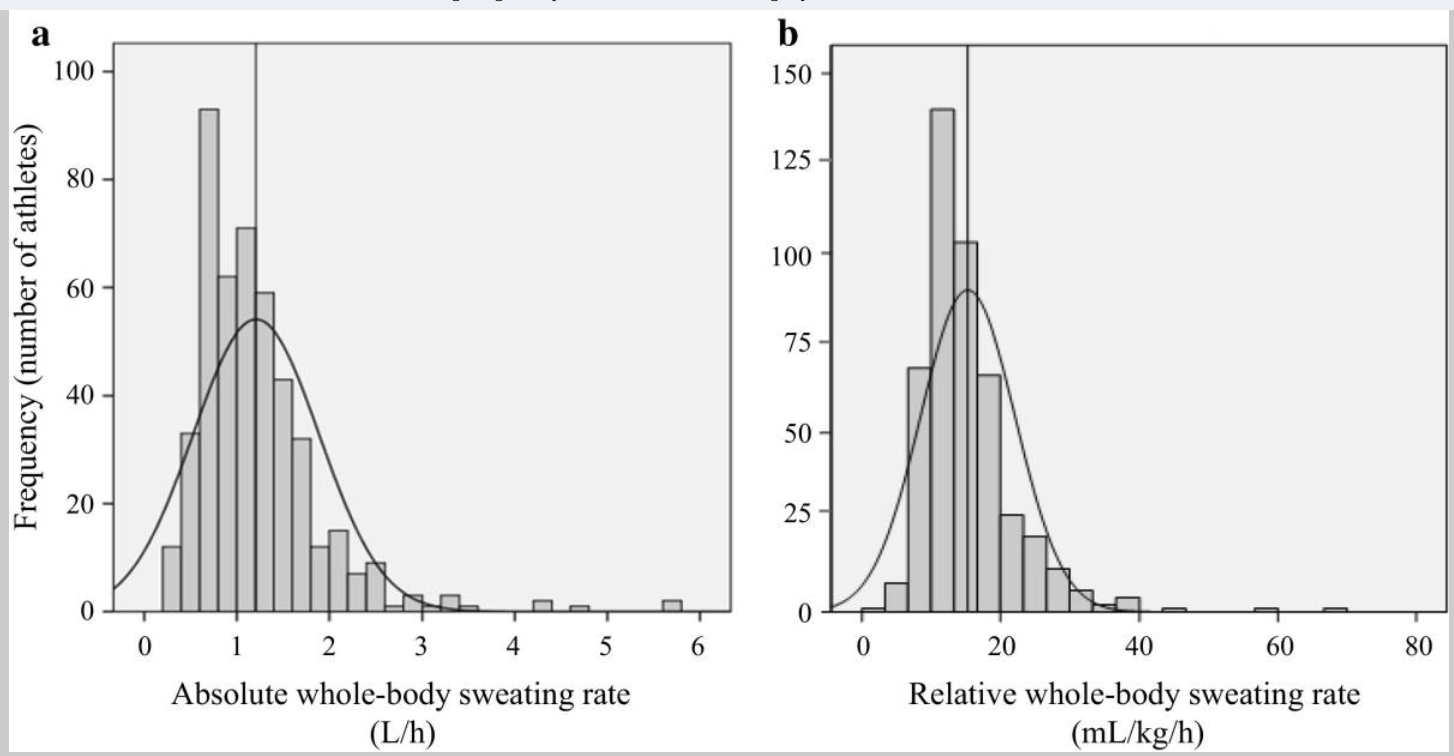

For general atheletes, 1 documented about ~0.5-3L/h water loss, which is a lot! I would expect durance runners to be on the high end of the chart.

In ACSM revised it’s guideline in 20072, it suggests to keep water loss within 2% of body weight. For a 70kg person, that’s just 1.4L of water, which probably won’t last 1 hour in a race!

More studies have since been carried out (e.g., 3), and found during a marathon race, top runners can lose 6.6%~11.7% body weight (the winner of 2009 Dubai marathon lost 9.8%). In [^4(], more extremed water loss was observed during ultramarathon (100 mile), where averaged 1-6% weight loss, so I suppose atheletes found the need to control the water replacement in order to keep performing.

So the take away:

- We are still exploring how our body response to water loss during endurance running. Don’t take guidance for granted.

- Our body can tolerate certain water loss, and that can vary.

- But, that does not mean it won’t impact your performance, or it won’t harm your body.

- The smaller weight loss for ultramarathon runners suggests that the extreme loss (6.6-11%) might not be sustainable for most runners, and for longer distance. Replacing water loss is crucial!

Weight loss does not equal to water loss

During long hard endurance running, both lean and fat of body can be decomposed for energy. During an ultramarathon, 2.6% of body weight can be lost from that (4). But that techincally shouldn’t be considered as water loss, just something to consider when interpretating weight loss numbers.

Interestingly, our body can typically store ~500g of glycogen, which is stored with 3 times of water. During exercise, it will be released as addtional water source (~1.5kg). Basically, you are carrying 1.5L of water supply within your body! That’s ~2% for many.

Tapering before race can add more to this reserve.

How much water loss is acceptable?

The short answer, it depends!

But in general (not accounting for extreme weather conditions):

- No need to drink if the exercise <1 hour.

- One can tolerate 2% (or maybe a bit more) of water loss without much issue.

- Try to drink to replace as much loss as possible, without causing much discomfort.

- Pay attention to the electrolyte balance.

Human sweat contains 0.9g/L sodium, 0.2g/L potassium, and many other electrolytes.

Symptoms of Dehydration

- Thirsty - of course. You probably should have drink before you feel thirsty.

- Heart rate increase while maintaining a similar pace. It is possible that you became very tied due to accumulation of blood lactate or simply run out of energy. But dehydration could also be a key contributor.

- Cramps - often a combination of dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

- Headache, foggy mind

- Ear discomfort - eustachian tube connects middle ears to the back of the throat, mainly to balance the air preassure. Dehydration can cause the tube to stay open, which is quite discomfortable and likely you can hear your heavy breath very clearly (running in cold weather can also contribute to that).

- Dark yellow urine

Symptoms of over-hydration - often hyponatraemia (low sodium/electrolyte )

Odd enough, it does happen! It share many similar symptoms with dehydration, or heat illness.

- Confusion - brain is often sensitive to low electrolyte level.

- Swollen fingers

- Nausea

- Stomach pain

- Cramps

- Feeling weak

Check contained electrolyte contents in sport drinks, salt tabs or energy gels.

Hydration Strategy For Long Races (e.g. Marathon)

The day before race

Make sure you are properly hydrated with some electrolytes the day before the race. May add a little more electrolyte to have some reserve.

Race day, before race

2-3 hours before the race: drink about 500ml of body weight in the morning.

Avoid drinking too much, which increases the chance of visiting the restroom during the race, and the chance of getting a blasted stomach. Also, avoid drinking pure water for the risk of hyponatraemia later.

If possible, drink a small amount (100-200ml) 15 mins before the race.

During race

The drinking strategy varies by person, so always plan your strategy be based on sweat test.

As discussed earlier, our body may not need 1:1 water replacement during the race. But if the duration is long, we should still target to replace close to 1:1 to avoid damage to our body and performance.

During the first 30 mins of the race, you don’t really need to drink. It is good to have a small sip early on, if it doesn’t slow you down.

Try sport drinks at least every other water stop for better electrolyte balance. Many people found it might make them more thirsty if take sports drinks every time.

Some tips:

- If you are a heavy sweater, consider bringing your own hydration pack.

- Along with hydration, consume some carbohydrates to fuel your body for better performance.

- When taking gels or food, pay some attention for the ingredients. Additional water may be required in order for digestion, which increased the needs for water.

- Try to grab some water in every water stop (unless it is packed with runners), and take small sips of water. Drinking too much at once may upset your stomach or making it difficult to breath.

After race

Drink enough to keep urine light yellow.

Sweat race test

- Take one’s pre-run weight (with minimum clothes on) - W1.

- After the run, shower and dry one’s body and measure body weight (again, with minimum clothes on) - W2.

- Measure every intake during the run (water and/or snack) - W3

Then you can calculate the sweat rate.

Sweat Rate (per body weight per hour) = (W1 + W3 - W2) / Run Duration In Hours.

To prepare for a race, it is best to perform the test in similar conditions (e.g., pace, weather, distance) to have a more accurate estimate.

For relatively shorter run, the sweat rate test might not be accurate because of the water from breaking down of glycogen (see above here).

References

-

Sweating Rate and Sweat Sodium Concentration in Athletes: A Review of Methodology and Intra/Interindividual Variability ↩

-

American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement ↩

-

Drinking behaviors of elite male runners during marathon competition ↩

-

Abstracts for the 4th Annual Congress on Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports, May 30, 2017, Denver, Colorado ↩